A Musical Journey through the Hustle

Table of Contents

“Hustle: the power to charge your life with money, meaning, and momentum” (the title of a self-help book), and similar promises have been championed by self-help experts, social media influencers, and even traditional elites – think politicians and corporate executives – in the last 5 years. Hustle culture, as we know it in the mainstream, is built upon an idealised, neoliberal narrative that any dream can come true with enough hard work. Hustling has become near synonymous with devoting extreme levels of effort in order to achieve said dream.

But before the glamorisation of the hustle, hustling used to be, and continues to be, about strategies of resistance and getting by amidst a backdrop of marginalisation and precarity. Isabella Rosario has written a brilliant piece detailing the evolution of the term – from an encapsulation of the realities of making ends meet as a poor Black person in the US, to its current co-optation (and increasing rejection) by a privileged class.

With that said, hustling has not been solely defined by acts of ‘doing’, moving or working. It has simultaneously been characterised as an emotive experience, values of resilience and creativity, identity-crafting, a shared culture, and so much more. As the concept has morphed across time and is exported beyond the context of poor urban neighbourhoods in the US, it has acquired a diverse set of meanings as it is reshaped to describe and connect with local lived realities. Tatiana Thieme contends that hustling is a ‘multi-sited and multi-vocal experience’ – everyone has their individual articulations of what hustling entails. The hustle of an investment banker in corporate America can look very different from the hustle of an independent filmmaker in Kenya.

The constellation of diverse experiences and definitions that are folded into the concept of a hustle can simultaneously be frustrating and productive. Though it leaves the concept nebulous and confusing to disentangle, housing these varied realities within a singular concept can be helpful in creating shared solidarity across geographies, class, and race. This entanglement forms the motivation of this article. I hope to explore how hustling is articulated and draw out commonalities and divergences in the ways hustling is narrated to provide some form of clarity to the concept.

Understanding the hustle through songs #

The popularisation of the hustle can be traced back to its use in hip hop songs of the 1990s and early 2000s. Songs were the main vehicle through which the hustle was introduced to the mainstream and exported, and they remain a key medium through which people narrate their experiences of hustling. This makes them a rich and apt data source to analyse how the hustle is articulated in everyday use and identify any continuities or deviations from its initial use in hip hop songs of the 90s.

As English is my first language, this analysis will focus solely on English songs, and consequently anglocentric conceptualisations of the hustle. Due to my linguistic limitations, I will not be able to explore non-English narrations of the hustle.

To unpack how hustling is portrayed through songs, I will discuss three sub-questions:

- Who is singing about the hustle?

- What are the most frequent themes that emerge?

- How do these themes differ by genre and popularity?

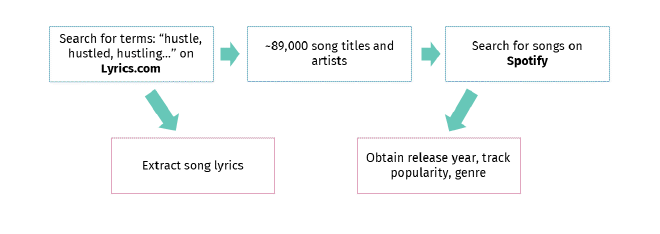

This article takes a quantitative approach to the exploration, which allows me to analyse the themes both at-scale and in-detail. To collect the data, I first used lyrics.com to search for a list of songs containing any conjugation of ‘hustle’ in its lyrics and extracted their lyrics. The next step was to search for these songs on Spotify to obtain the data on their release year, popularity, and genre. From there, a random sample of 10,000 songs were selected out of the initial 89,000 for further analysis. Data collection was conducted via web scraping and the Spotify API.

To provide a background into the distribution of songs that will be discussed, I will start with basic descriptive analysis of the songs within the sample.

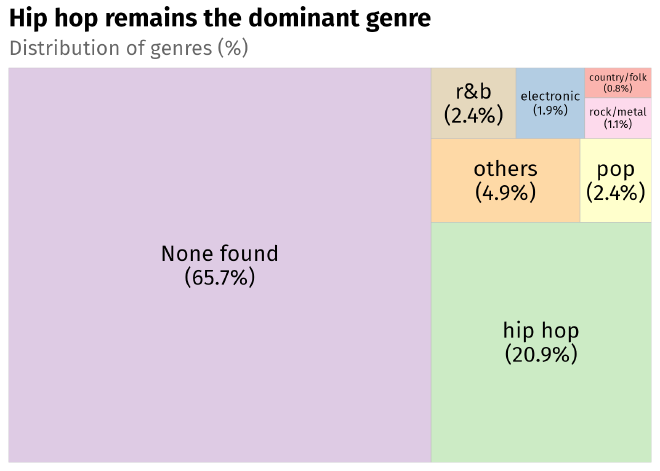

A large majority of songs do not have a genre provided as the artist and song are relatively unknown, and thus not tagged by Spotify. The ‘none found’ genre could thus be interpreted as an indicator of a relatively underground or unknown song. Within songs that have genre data, hip hop is the most represented genre by an overwhelming margin. This may be indicative that despite the expansion into the mainstream, hustle remains heavily intertwined with hip hop culture. Artists outside the genre may not identify with the hustle enough to make a song to articulate their experience.

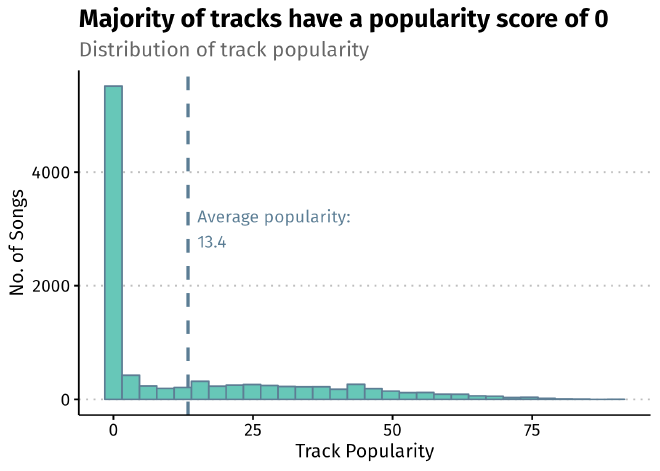

Song popularity ranges from 0 to 100 and tracks how popular a song is, relative to others. Most songs captured are relatively unpopular and have very few plays (<5000). Thus, the data collected includes narrations that are less surfaced and allows for a deviation away from dominant portrayals that traditionally fill the airwaves.

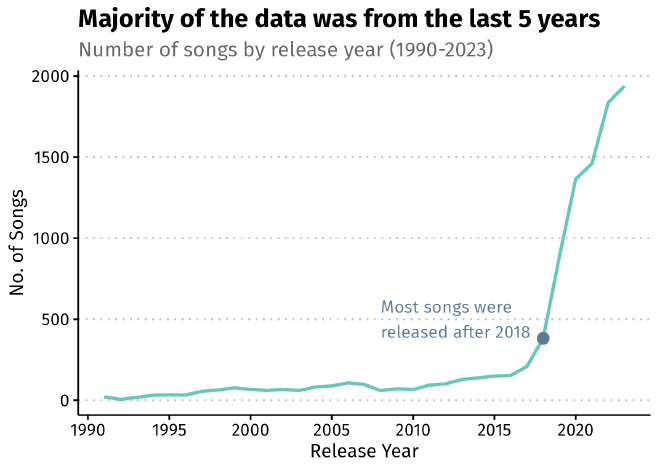

Most of the songs extracted are from 2019 onwards, likely reflecting a recency bias in both lyrics.com and Spotify, where older songs are unlikelier to be on either platform. Due to this extreme skew, release year will not be analysed as a factor affecting the prevalence of themes across songs.

Who is “doin’ the hustle”? #

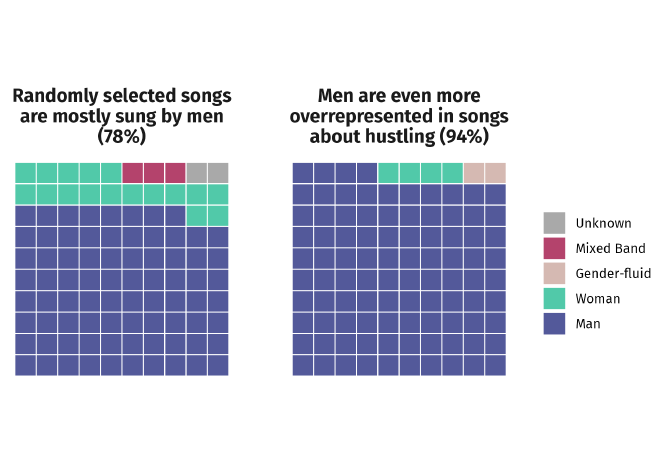

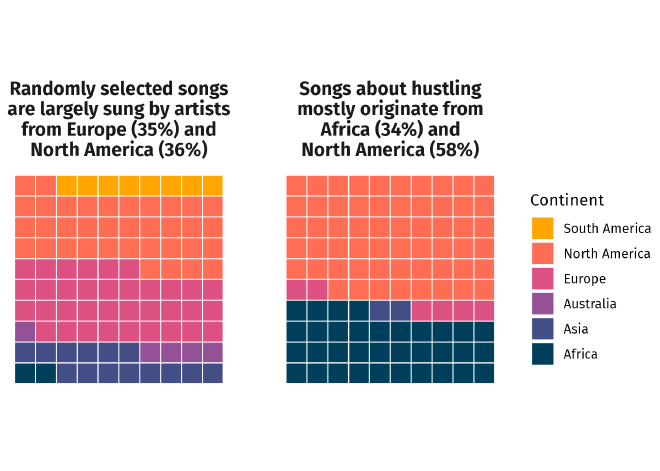

From the 10,000 ‘hustle’ songs, a random sample of 100 songs is taken and manual searches on the artist’s gender and country of origin are conducted. This is compared against 100 randomly selected Spotify tracks, generated using this website, which serve as a baseline for comparison.

While random Spotify tracks are already male dominated, this skew is even more extreme for songs that discuss the hustle. This supports a growing body of literature exploring the gendered nature of hustling, where accounts of hustling are overwhelmingly male dominated. It seems that the hustler is an image reserved for men and is more closely tied to a traditional notion of masculinity in terms of provision for the family. The skew indicates that women are less likely to narrate their experiences as a ‘hustle’ and may take on adjacent images such as that of a ‘girlboss’. Or as Beyonce puts it, “diva is a female version of a hustla”.

Hustling is overwhelmingly narrated by artists from North America and Africa. As the birthplace of the hustle as we know it, North America is an unsurprising candidate for the top spot. The wide difference in representation of African artists seems indicative that the hustle is a key theme of narration for African artists.

Naomi van Stapele writes about a sense of ‘diasporic intimacy’ that helped hustling travel from marginalised urban spaces in the US to those in African cities. The echoes in racialised experiences, systemic neglect, and living from the fringes create strong resonance for the concept. This also supports the growing body of literature exploring how hustle culture has become an important identity marker for youths in African cities and a central organising principle of urban living, much like the experience of Black people hustling in impoverished neighbourhoods in the US.

The hustle, at least within music, seems to be a gendered concept largely narrated by men, is strongly associated with hip hop culture, and has strong links to diasporic identities as it is mostly articulated by Black men from North American and African cities. Despite the adoption of the concept into the mainstream, its narrators – at least within the music scene – have not deviated far from the initial wave of songs about hustling.

What is the ‘hustle’? #

To answer this, the songs will be analysed through structural topic modelling, a computational approach to extract common themes that emerge across the sample of 10,000 songs. In brief, structural topic modelling is an exploratory tool that allows the researcher to discover at scale the topics that a set of texts discuss. It does this by finding sets of words that tend to occur together and puts them into groups (topics). The algorithm is only capable of grouping the words together, but substantive interpretation on my end as the researcher is required to understand what each topic means. These topics, however, may not always be meaningful. The words and songs most associated with each topic are analysed and interpreted to make sense of what the groups of words indicate and put a label on them.

The model also provides a prevalence score that shows how prevalent each topic is for each song, which can be thought of as the percentage comprised by a song. This allows us to analyse and compare topic prevalence based on song characteristics such as genre or popularity to identify potential divergences in the narration of hustling.

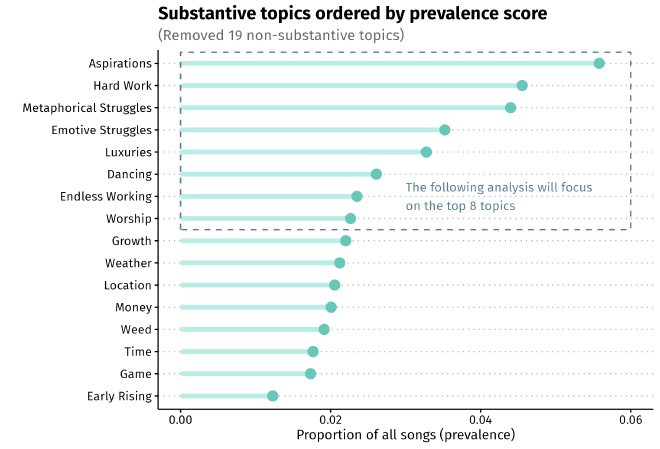

The full list of topics includes a few groups of words that do not discuss any concept or theme in particular but contain sets of words that are commonly used in conjunction. For instance, curse words and contractions each have their own topics. These non-substantive topics are excluded from the graph and the analysis.

Some popular themes include aspirations, working hard and the ‘grind mentality’, struggles and emotions, and enjoyment relating to luxuries and dancing. Of note, there is also a considerable prevalence of worship and mentions of faith. Henceforth, I discuss the eight most prevalent topics and analyse what they tell us about common narrations of hustling.

Aspirations #

The most prevalent topic across all songs discusses aspirations for a better life. It comprises hopeful language like ‘dreams’, ‘living’, ‘success’, ‘rise’, ‘survive’ to denote a goal to ‘hustle’ towards. The words seem to indicate a range of aspirations – from survival, to more idealistic or lofty goals of achieving one’s dreams.

| life, never, keep, live, make, gonna, living, people, dreams, try, just, world, change, going, struggle |

| dreams, live, forever, living, life, rise, gonna, pushing, survive, seems, sometimes, struggles, focus, success, never |

| (FREX picks up words that are common in the topic and unique relative to other topics) |

One of the songs with the highest prevalence of aspiration is Bumpy by SAB, a Ugandan artist. SAB sings that “the hustle’s for survival it’s do or die in the street…We’ll find a way to conquer our dreams and souls we’ll keep”.

This narration of hustling largely aligns with ethnographic accounts of the hustle within the literature and reflects the experiences of underemployed youths in underserved urban neighbourhoods, where there are overlapping aspirations relating to the hustle. Most pressingly, the hustle is about survival – it is about finding any opportunity possible to make ends meet. But beyond that, the hustle also encompasses an aspirational element of achieving sufficient freedom to pursue ambitions and interests. As Grace Mwaura finds, aspirations and dreams are a means through which youths ‘fulfil their imaginations’ to keep their souls (in the words of SAB) and is a tool for identity-making. Beyond being defined by unemployment or survival, the hustle allows them to identify as empowered roles of dreamers and entrepreneurs.

Aside from the hustles of the African youths as narrated by SAB, an aspirational element is equally important to other models of the hustle - such as that of the university side-hustler. The hustle is framed as ‘aspirational labour’, where the hustle is centred around a passion or dream, while university is a fall-back to accommodate the hustle.

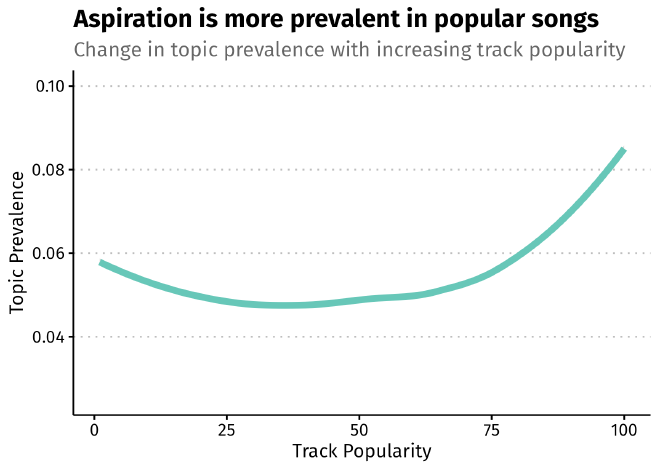

The model finds that the prevalence of aspiration increases with rising track popularity. The more prevalent aspiration is, the more popular the song is. It seems that aspiration is not only a topic commonly narrated by multiple artists, but also resonates with the medium’s consumers and is highly well-received. The high prevalence and popularity of the aspirational dimension indicates that aspiration cuts across different experiences of hustling and is a principle constituent of the hustling experience.

Working Hard #

Hard work is the next most prevalent topic across all songs. There are two topics relating to hard work. The first topic comprises active language about getting things done such as “gotta”, “grind”, “work”, “hard”. The second topic comprises temporal-based woords that relate to ideas of ceaseless productivity that have been attached to hustle culture: “everyday”, “day”, “night”.

| get, gotta, hard, grind, work, hustle, stop, got, stay, till, getting, keep, make, paid, imma |

| gotta, grind, get, work, paid, hard, stop, till, imma, mission, ambition, stay, eat, shine, stopping |

| one, day, every, night, everyday, another, pay, days, hustle, just, grinding, hustling, working, way, sleep |

| day, night, every, one, another, everyday, grinding, hustling, lovely, days, single, working, pay, monday, sunday |

In “Get It”, NudeBillions pits the White, middle-class standard of waged employment against the hustle, singing that “you gotta get it / you can work a 9 to 5 / or you can hustle”. He speaks to an entrepreneurial element and informality of the hustle, where work occurs beyond conventions of waged employment.

Similarly, FILLUP Bank$ sings “all I know is hustle hard and work my ass off / you don’t see nobody giving me no handouts” in his song, Go Get It. He pits the hustle and hard work against the idea of receiving ‘free’ assistance from others.

In narrating the value of hard work, both singers establish a counterfactual for the hustle, a ‘failure’ that either involves having to work for someone else or having to receive a handout from someone else. Both depictions elevate the importance of the individual, perpetuating what Demetrius Noble describes as an individualisation of success and failure, and trivialisation of systems and structures. Thus, hard work is imbricated with ideas of the individual and hyper-individualisation.

The model shows that these individualised narratives of hard work have come to dominate accounts of the hustle, aligning with mainstream notions of the hustle culture.

While hard work may seem to be a common theme narrated across the hustling experience, Mark Anthony Neal contends that the popularisation of this narrative within commercial music is driven by the “engines of global corporate capitalism”. The articulations appeal to popular neoliberal ideologies in order to serve the mainstream audience who would be uncomfortable with critiques of the structural oppression that underpin the hustle.

That is to say, while hard work and individualisation are strong themes within songs, there is room to question the extent to which its prevalence is reflective of the salience of hard work in artists’ personal encounters with the hustle and the extent to which it is played up for mass appeal.

Emotive struggles #

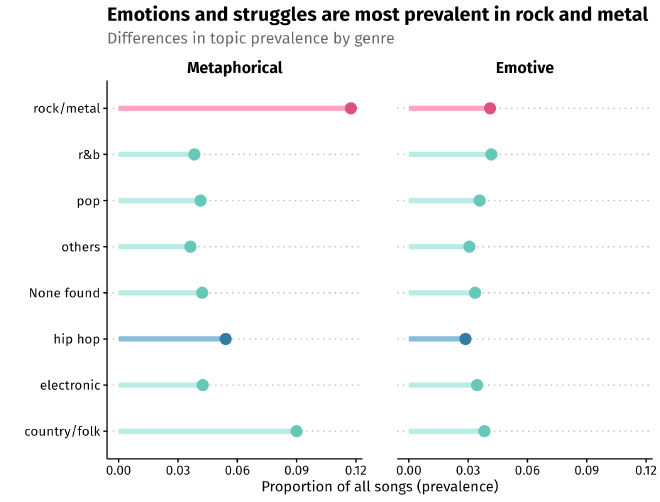

Struggling and feelings of pain are another common theme across songs discussing the hustle. The first topic speaks to more metaphorical languages of “puzzle”, “black”, “hearts”, “broken”. while the second topics evokes more emotive language in “pain”, “eyes”, “nobody”, “feel”.

| still, can, trouble, light, new, now, black, just, see, look, next, let, word, soul, double |

| puzzle, legacy, knowledge, american, trouble, broken, thoughts, hearts, connected, others, upgrade, planet, subtle, earth, least |

| see, can, better, everything, pain, nobody, believe, away, will, mama, feel, eyes, look, win, wish |

| pain, believe, wish, away, win, everything, eyes, energy, nobody, blessed, better, times, will, save, today |

For instance, V-FLO sings poignantly about the pain and struggle attached to the hustling experience. “It’s a nonstop hustle / it’s a nonstop grind / Man you can not feel my pain but you can see it in my eyes…They don’t understand the struggle / They don’t understand the pain”

The prevalence of the two topics support the view that the hustle is more than survival, getting by, or working hard. It is also an emotive experience. Rather surprisingly, this emotive aspect is commonly narrated in songs, which runs contrary to the glorification of the hustle seen over the last 5 years.

However, its prevalence differs significantly by genre. While metal and rock music tend to see higher proportions of discussions around struggles through both emotive and metaphorical language, hip hop tends to veer away from discussing their struggles using emotive language, relative to other genres. This potentially relates to the performative aspects of how the hustle is narrated.

Depending on genre conventions and expectations, hustling can be articulated in different ways. In hip hop, the hustler is commonly pictured as the idealised, successful Black man – an ideal that often goes along with an image of masculinity and stability. This convention of the hustler runs contrary to the emotive aspects of hustling, which may be why emotive language sees less use in hip hop.

Worship #

The model shows that there is a considerable prevalence of references to faith and God through words such as “god”, “bless”, and “oluwa” - a Yoruba word referring to God.

| god, pray, bless, make, oluwa, baba, hustle, blessings, ooo, say, grace, blessing, pay, jah, ohh |

| bless, oluwa, blessings, grace, pray, ooo, blessing, ohh, amen, ehh, baba, jah, shower, god, prayer |

This opens up an interesting topic on the relation between faith and hustling. While there is some literature on evangelical hustling, or “hustling to get the Word out”, there is also an element of faith and worship that can play into non-evangelical hustles. Faith-based belief systems are also articulated as a system of support to get through the hard work and endless productivity that hustling demands. There is potential to further explore how religion and faith shape the hustling experience, and vice-versa.

So what? #

This article in no way meant to be a conclusive piece of work about what hustling means. While I have found data that support existing bodies of literature, what is arguably more important, is the discovery of potential strands for new research as hustling continues to evolve in its use.

One significant finding is that while the hustle has gone mainstream, its narration - at least within songs - remains largely reflective of the male, afro-diasporic experience. Its articulation appears to be heavily gendered and racialised, and there is room to investigate whether (and why) other singers may not be using the term ‘hustle’ to describe their experiences.

Across the varied encounters with hustle across 10,000 songs, three common themes emerge: aspirations, hard work, and struggles. While aspirations and hard work affirm mainstream narratives surrounding individualised success and work, the theme of struggles indicates that hustling is also commonly narrated as an emotive experience in songs. The emotive experience seems to be a blindspot in most other mediums of narration and deserves further attention on the specific emotional journeys that accompany, shape, or are a result of the hustle. An additional theme for exploration was also identified in worship and faith.